Why Weight Loss Doesn’t Always = Better Performance

It’s should come as no surprise that in endurance sports (amongst others), power to weight ratio is a key determinant of an athlete’s performance. Look at the podium of any grand cycling tour, marathon or triathlon and you’ll likely see an incredibly lean athlete who’s able to produce high work rates. As such, it comes as little surprise that many athletes look to try and optimise their body compositions in the pursuit of increased performance.

Weight Loss

Due to the potential to improve performance and the culture within the sport, athletes and coaches are often pre-occupied with disciplined training diets and the pursuit of weight loss, with weight loss often a go to performance enhancer. However, rarely are the downsides of the pursuit of weight loss discussed or taken into account when selecting this as a tool for performance enhancement. For a number of reasons, weight loss can actually lead to significant reduction in performance, as well as significantly negatively impacting on an athletes health.

To achieve weight loss we need to be in a calorie deficit, whereby we expend more energy than we take in through food. Endurance athletes often end up in a calorie deficit through one of two way. 1, the conscious restriction of energy intake through reducing food intake and 2, through inadvertently not consuming sufficient energy to meet the demands of their training/competition. Being in a calorie deficit can lead to an athlete being in a state of low energy availability.

Low Energy Availability, Health & Performance

Energy availability refers to the calories that an athlete has left once their energy expenditure from exercise has been taken into account. For example, on a given day, if an athlete completes a hard training session that expends 2000kcal during the training session alone, but only consumes 2500kcal within that day, their energy availability is a mere 500kcal. Energy availability is normally expressed relative to an individual’s Fat Free Mass (basically all the tissue within the body that isn’t fat) and below a threshold of 30kcal/kilograms body weight /fat free mass/per day, is considered low energy availability.

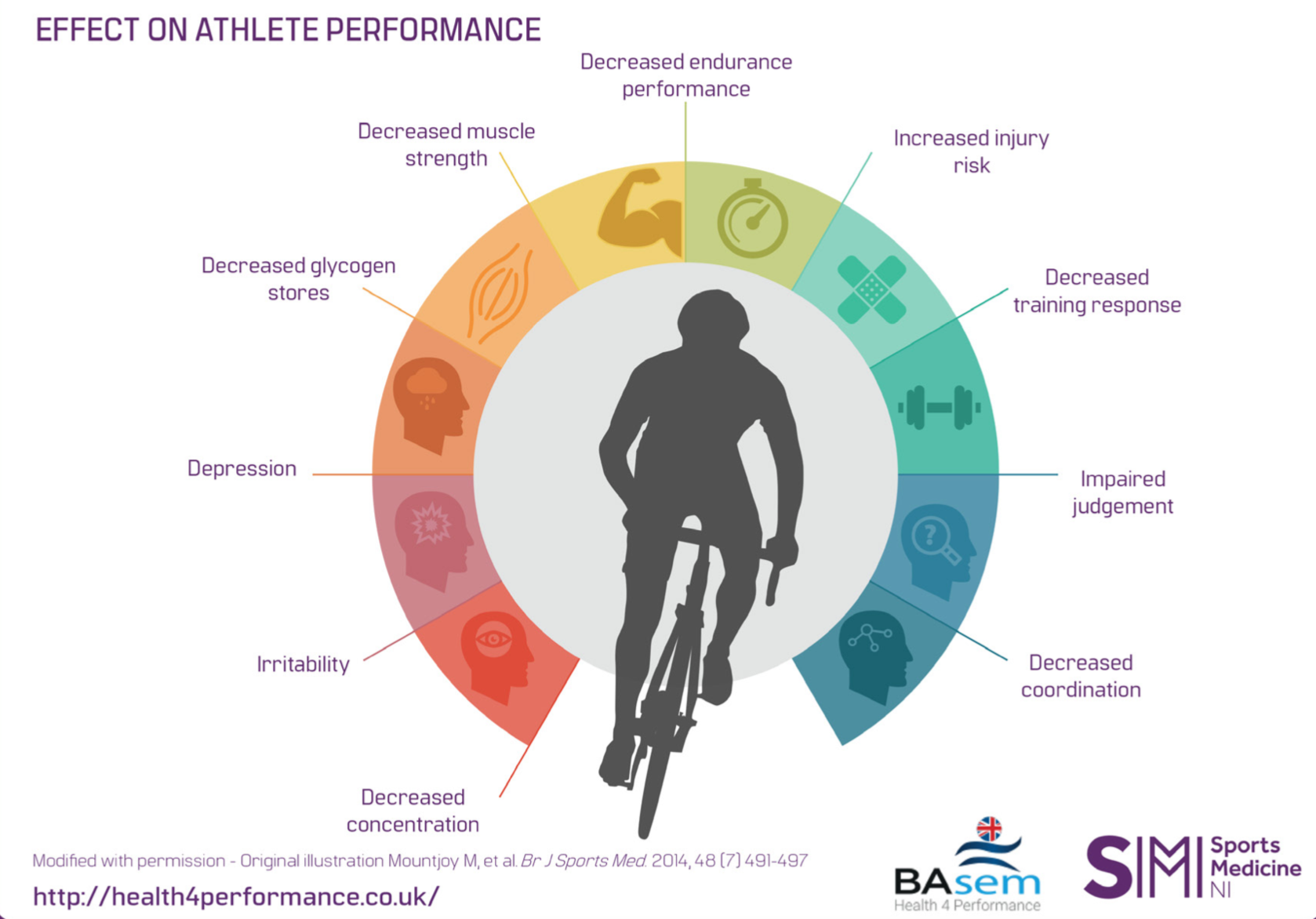

Low energy availability can result in RED-S. Referred to as relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S for short), the syndrome is associated with a number of negative effects on an athletes health and performance as illustrated in the two spoke and wheel diagrams below.

A number of high-profile examples of athletes who have experience RED-S have been reported within the media, with athletes often experiencing serious negative health consequences.

Road Cycling, Nutrition & Performance Study

A growing body of sports science research is now also illustrating to us why the pursuit of weight loss (and resultant cumulative low energy availability state an athletes ends up in) isn’t always performance enhancing, and why athletes potentially stand to gain more from optimal fuelling their training and racing than they do trying to lose a few kgs.

Our best illustration of this to date, particularly in the sport of road cycling, comes from a fascinating study from Endocrinologist Dr Nicky Keay and colleagues in 2019 (1). The study took 45 male cyclist who where Category 2 and above, including a number of Elite World Tour Cyclist. The riders where screened at the start and end of the race season for their performance using a functional threshold power test, bone health (a key indicator of low energy availability, insufficient energy = poor bone health) using a DEXA scan and their energy availability using a questionnaire and interview. They also had bloods taken for screening of metabolic and endocrine markers, which are often related to RED-S. They were then divided into pairs matched for their bone health results, with one from the pair left to their own devices for the season and the other given an educational intervention around how to optimally approach their training nutrition, with a focus on optimal fuelling to avoid them being in low energy availability combined with some exercises designed to load the skeleton in an effort to improve bone health (n.b. Cyclists generally have poor bone health due to a lack of skeletal loading and at times low energy availability).

At the end of the season, the athletes returned to the lab and where screened again. Despite the instructions from the study, many athletes didn’t follow the advice they were given, so the numbers weren’t quite matched to the original plan, however the follow up revealed some interesting findings…

1. The 11 cyclists who made positive changes to their nutrition behaviours and off the bike exercise, reported improved well-being and feeling stronger on the bike.

2. Despite no athletes in the study being told to reduce their nutrition intake or reduce off bike exercise, nine athletes did in the belief it would improve their performance but all reported fatigue, illness and injury.

3. Increasing off the bike exercise and nutrition intake resulted in improvements in the athlete’s bone health, whilst reducing off the bike exercise and nutrition intake did the opposite.

4. The results suggested that improving energy availability was worth 95 British Cycling Racing points, whereas restricting nutrition cost 95 points.

Take Home Points

So in effect, if you’re a relatively lean athlete already that performs at a high levels and you want to improve your performance, feel better on the bike, improve your bone health, reduce your ride of illness and injury then you’d be better focusing on optimally fuelling your training and competition than the pursuit of weight loss.

References

Keay N, Francis G, Entwistle I, Hind K. Clinical evaluation of education relating to nutrition and skeletal loading in competitive male road cyclists at risk of relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S): 6-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2019;5(1):e000523. Published 2019 Mar 29. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000523

More resources on RED-S - http://health4performance.co.uk / https://red-s.com